When to treat?

Preparing Apiguard …

When and how do you treat colonies to have the greatest effect in minimising Varroa levels? At the end of this longer than usual post I hope you’ll appreciate that this is a different – and much less important – question than “When is the best time to treat?”.

You probably use one of the treatments licensed and approved by the Veterinary Medicines Directorate (VMD), which include Apistan, Apivar, Apiguard, MAQS and Api-Bioxal. I’ve discussed the cost-effectiveness of these treatments recently. If used correctly, all exhibit much the same efficacy, reducing phoretic mite levels by 90-95% under optimal conditions. That being the case the choice between them can be made on other criteria … the ease of administration, the cost/treatment, the likelihood of tainting the honey crop, the compatibility with brood rearing, whether they mess up your vaporiser etc. After using Apiguard for several years, with oxalic acid (OA) dribbled in midwinter, my current preference – used throughout the 2015 season – is OA sublimation or vaporisation. This change was based on four things – efficiency, cost, ease of administration and how well it is tolerated by a laying queen. The how? you treat is actually reasonably straightforward.

When, not how, is the question

DWV symptoms

OK, but what about when? Because, if the treatments are all much of a muchness if used correctly, the when is actually the more important consideration. When might be partly dictated by the treatment per se. For example, Apiguard needs an active colony to transfer the thymol throughout the hive so the recommendation is to use it when the ambient temperature is at least 15ºC (PDF guidance from Vita). It’s worth stressing that this is the ambient temperature, not the temperature in the colony, which in places will be mid-30’s even when it’s much colder outside. At low ambient temperatures the colony becomes less active, and in due course clusters, meaning that Apiguard is not spread well throughout the colony, and is therefore much less effective. If you’re going to use Apiguard you must not leave treatment too late.

For readers in Scotland it’s interesting to note that the SBA annual survey by Peterson and Gray shows significant numbers still use Apiguard in September and October, months in which the mean daily maximum temperature is ~14°C and 11°C respectively … so the average daily temperature will be well below the recommended temperature for effective Apiguard use.

However, the when should be primarily informed by the why you’re treating in the first place. It’s not really Varroa that’s the problem for bees, it’s the viruses that the mite transfers between bees when it feeds on developing pupae that cause all the problems. Most important of these is probably Deformed Wing Virus (DWV), but there are a handful of other viruses pathogenic to bees that are also transmitted. DWV causes the symptoms shown in the image above … these bees are doomed and will be ejected from the hive promptly. However, although apparently healthy (asymptomatic) bees have low levels of DWV, it’s been shown by Swiss researchers that DWV reduces the lifespan of worker bees, and that high levels of DWV in a colony are directly associated with – and causative of – overwintering colony losses. Therefore, the purpose of late summer/early autumn treatment is to reduce the Varroa levels sufficiently so that high levels of the virulent strains of DWV are not transmitted to the overwintering bees. When? therefore has to be early enough that this population, critical for overwinter survival, will live through to the spring – however long the winter lasts and however severe it is. However, before discussing when winter bees are reared it’s worth considering what happens if treatment is used early or late.

What happens if you treat early?

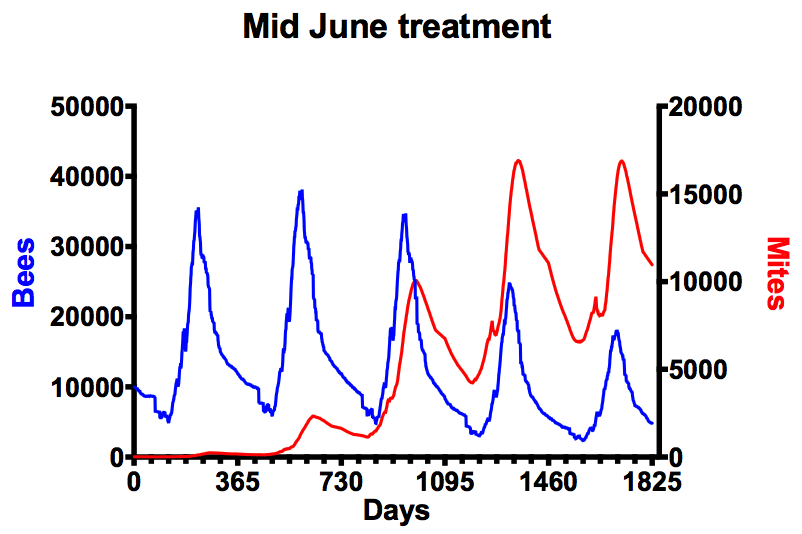

Mid June treatment …

For example, mid-season or after the first honey crop comes off. Nothing much … other than slaughtering many of the phoretic mites. This is what most beekeepers would call “a result” 😉 Aside from possible undesirable side effects of treatment – like tainting honey, or preventing the queen from laying or even, with some treatments, queen losses – early treatment simply reduces mite levels. It’s important to remember that the levels may well not be reduced sufficiently to negate the need for a treatment later in the season … as long as there is brood being raised the mites will be reproducing (for example, look at the mid-June treatment generated using BEEHAVE modelling – image above). Furthermore, avoiding those undesirable side effects might require some ‘creative’ beekeeping (for example, clearing the supers and moving them to another hive) and will certainly inform the choice of treatment but, fundamentally, if the mite levels are high then treating earlier than is usual will benefit the colony, at least temporarily. If the mite levels – estimated from the disappointingly inaccurate (deleted broken NBU link ... sorry ... try this more recent post instead) mite drop perhaps – are dangerously high you should treat the colony.

What happens if you treat late in the season?

Isolation starvation …

In midsummer workers only live for ~40 days. If mite levels are high, virus transmitted to these workers will shorten their lives, so reducing the colonies’ foraging ability and – possibly – ability to defend itself against wasps or robbing late in the season. However, if you delay treatment until very late the lifespan of bees raised at the end of the season – the overwintering bees – will be reduced with potentially more devastating consequences. The usual winter attrition rate of workers will be higher. The cluster size of the colony will shrink faster than a colony with low mite levels. At some point the colony will cross a threshold below which it becomes non-viable. The cluster is too small to move in cold periods to new stores, resulting in the beekeeper finding a pathetic little cluster of bees in a colony that’s succumbed to isolation starvation. A larger cluster, spread across a greater area and more frames, is much more likely to span an area of sealed stores and be able to exploit it.

When are winter bees reared?

Frosty apiary

In the Swiss study referred to above they looked at the longevity of winter bees. The title of the paper is “Dead or alive: deformed wing virus and Varroa destructor reduce the life span of winter honeybees”. We can use their data to infer when winter bees start to be reared in the colony and when mite treatments should therefore have been completed to protect these bees. Their studies were conducted in Bern, Switzerland, in 2007/08 where the average temperature in November/December that year was 3ºC. They first observed measurable differences in winter bee longevity (between colonies that subsequently succumbed or survived) in mid-November. This was 50 days after bees emerged and were marked to allow their age to be determined. By the end of November these differences were more pronounced. Therefore, by mid-November Varroa and virus-exposed winter bees are already exhibiting a reduced lifespan. Subtracting 50 days from mid-November means these bees must have emerged in late September. Worker development takes ~21 days, so the eggs must have been laid in the first week of September, and the developing larvae capped in mid-September.

To protect this population of overwintering bees in these colonies, mite treatments would have had to be completed by the middle of September, so that mite levels were sufficiently low that the developing larvae weren’t capped in a cell with a Varroa mite carrying a potentially lethal payload of DWV. For Apiguard treatment (which takes 2 x 14 days) this means treatment should have been started in mid-August. For oxalic acid vaporisation (which empirical tests suggest is best conducted three times at five day intervals) treatment would need to start no later than early September and preferably earlier as it is effective for up to a month.

Of course, these figures and dates aren’t absolute – the weather during the study would have influenced when the larvae would be raised as winter bees, with the increased fat deposits and other characteristics that are needed to support the colony survival through the winter. Despite the study being based in Switzerland my calculations on dates are probably broadly relevant to the UK … for example, the temperature during their study period is only about 1ºC lower than the 100 year average for Nov/Dec in Eastern Scotland where I now live.

In conclusion

That was all a bit protracted but it hopefully explains why it’s important to be selective about when you administer Varroa treatments. Chucking in a couple of trays of Apiguard in mid-August or mid-October has very different outcomes:

- in mid-August the phoretic mite population should be decimated, reducing the transmission of virulent DWV to the all-important winter bees that are going to get the colony through the winter. This is a good thing.

- in mid-October the mite population will be reduced (not decimated, as it’s probably too cool to effectively transfer the thymol around the hive – see above) but many of the winter bees will already have emerged, probably with elevated levels of DWV to which they will succumb in December or January. This is a bad thing.

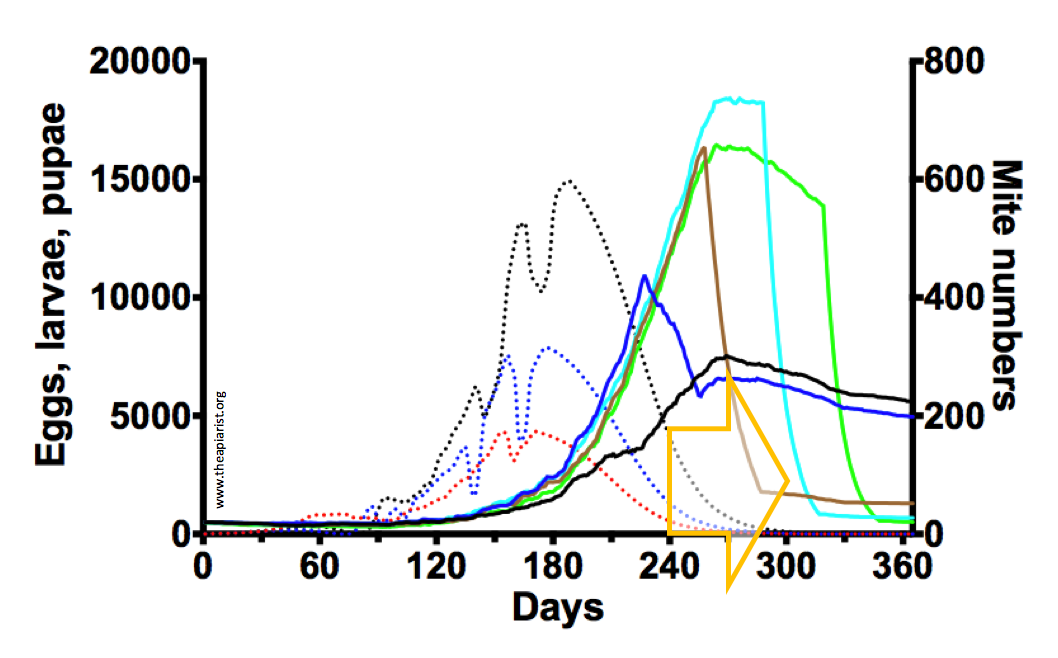

Perhaps perversely, treating early enough to prevent the expected Varroa-mediated damage to developing winter bees is not be the best way to minimise mite numbers in the colony going into the winter. Using BEEHAVE I modelled the consequences of treating in the middle of each month between August and November¹. I used the default BEEHAVE setup as described previously. Figures plotted are the average of 3 simulations, each ‘primed’ with 20 mites at the start of the year.

Time of treatment and mite numbers

There’s a lot on this graph. To show colony development I plotted numbers of eggs, larvae and pupae (left axis) as dotted red, blue and black lines respectively. Mite numbers are shown in solid lines – treated with a generic miticide in mid-July (black), mid-August (blue), mid-September (brown), mid-October (cyan) and mid-November (green). In each case the miticide is considered to be 95% effective at killing phoretic mites. The gold arrowhead indicates the period during which winter bees are developing in the colony, based upon the data from Dainat.

Oxalic acid trickling

Treating at or before mid-August controls the late-summer build up of mites in the colony – look how the blue line changes direction. Mites that are not killed go on to reproduce in late September and early October, resulting in levels of ~200 at the year end. Remember that mites present in midwinter can, in the absence of sealed brood, be effectively controlled by trickling or vaporising oxalic acid (Api-Bioxal), and that this Christmas miticide application is particularly important if the autumn treatment has not been fully effective. In contrast, treating as late as October and November (cyan and green lines) exposes the developing winter bees to the highest mite levels that occur in the colony doing the year, and only then decimates the phoretic mite numbers, with those that remain being unable to reproduce effectively as the brood rearing period is almost over. Starting treatment in mid-September isn’t much different, in terms of exposing the winter bees to high mite levels, than starting later in the year.

So, within reason, treating earlier rather than later both reduces the maximum mite levels and helps protect the winter bees from virus exposure. Of course, treating as early as mid/late August may not be compatible with your main honey crop (particularly if you take hives to the heather) … but that’s another issue and one to be addressed in a future post.

STOP PRESS There is a very important follow-up article to this. Kick ’em when they’re down describes why it’s so important to treat during a broodless period in midwinter to minimise mite numbers at the start of the following year. Just treating in late summer is not sufficient … you’ll protect your winter bees, only for them to be targeted by mites the following Spring.

¹BEEHAVE makes a distinction between ‘infected’ and ‘uninfected’ Varroa, the proportions of which can be modified. This might (no pun intended) not accurately reflect the reality in the hive, where Varroa-mediated transmission of DWV results in the preferential amplification of virulent strains of the virus. I need to roll my sleeves up and delve into the code to see if the model can be altered to fully reflect our current understanding of the biology of the virus. This might take quite a while …

References

Overwintering honey bees: biology and management from the Grozinger lab.

Managing Varroa (PDF) by the National Bee Unit

Join the discussion ...